import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Let's prepare a set of "semi-continuous" values to interpolate on.

x = np.linspace(0, 200, 100)

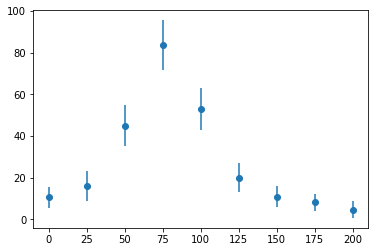

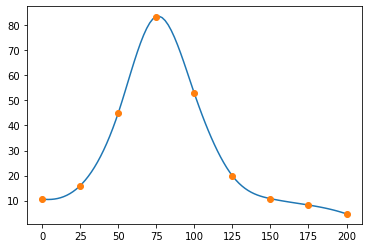

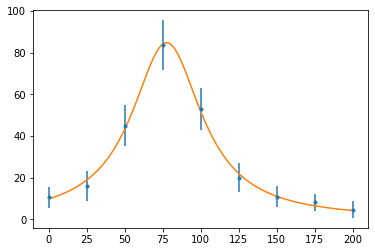

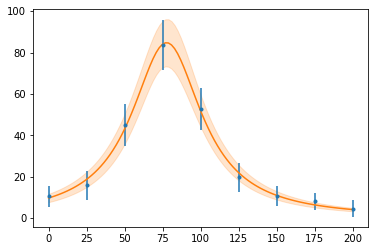

And, here's the data for a cross-section of resonant scattering of a neutron from a nucleus.

x_data = np.linspace(0, 200, 9)

y_data = np.array([10.6, 16.0, 45.0, 83.5, 52.8, 19.9, 10.8, 8.25, 4.7])

# e_data = np.array([9.34, 17.9, 41.5, 85.5, 51.5,

# 21.5, 10.8, 6.29, 4.14])

e_data = np.array([5, 7, 10, 12, 10, 7, 5, 4, 4])

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x_data, y_data, e_data, fmt="o")

plt.show()

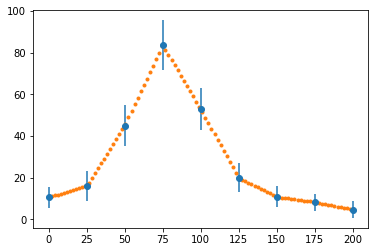

y = np.interp(x, x_data, y_data)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x_data, y_data, e_data, fmt="o")

ax.plot(x, y, ".")

plt.show()

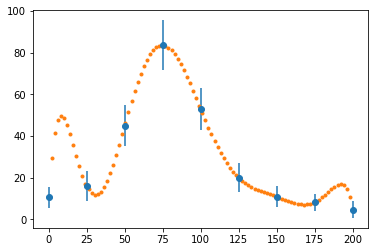

def interp_langrange(x_data, y_data, x):

"A custom Lagrange interpolate function."

# The shape will be N x N x n, where N is the number of points

# in x and y, and n is the number of points in the result.

x = np.asarray(x)

x = x.reshape(1, 1, -1)

# Make grid. Have one "throw away" diminsion to make [N,N,1] shaped arrays

x_n, x_i, _ = np.meshgrid(x_data, x_data, np.array([1]))

# Using a mask here avoids numpy warnings and makes the product easy

x_n = np.ma.array(x_n, mask=np.eye(x_data.shape[0]))

x_i = np.ma.array(x_i, mask=np.eye(x_data.shape[0]))

V = (x - x_n) / (x_i - x_n)

v = np.prod(V, axis=1).data # Convert back to non-masked arrays

return y_data @ v

# This was added to test interp_langrange

x_d2 = np.array([0, 1, 2, 4])

y_d2 = np.array([-12, -12, -24, -60])

interp_langrange(x_d2, y_d2, [0.5, 4]) # should be -10.125 and -60

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x_data, y_data, e_data, fmt="o")

ax.plot(x, interp_langrange(x_data, y_data, x), ".")

plt.show()

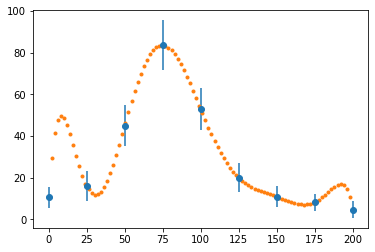

Of course, you shouldn't be writing your own algorithms for something that is generally useful - it's included in SciPy. Let's see what that would have looked like instead:

from scipy import interpolate

p = interpolate.lagrange(x_data, y_data) # Makes a callable object "p"

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x_data, y_data, e_data, fmt="o")

ax.plot(x, p(x), ".")

plt.show()

spline = interpolate.CubicSpline(x_data, y_data)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(x, spline(x))

ax.plot(x_data, y_data, "o")

plt.show()

from scipy.optimize import curve_fit

Our fit function is a theoretical model: a Breit-Wigner resonance:

$$ f(E) = \frac{f_r}{\left(E-E_r\right)^2 + \Gamma^2/4} $$def f(E, f_r, E_r, Γ):

return f_r / ((E - E_r) ** 2 + Γ ** 2 / 4)

Now, we look up the definition of curve_fit (using shift-tab, curve_fit?, or help(curve_fit)), and then feed it the parameters it wants:

popt, pcov = curve_fit(

f, x_data, y_data, p0=[1.0, 1.0, 1.0], sigma=e_data, absolute_sigma=True

)

It returns two objects; the array of fit value, and a covariance matrix.

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x_data, y_data, e_data, fmt=".")

ax.plot(x, f(x, *popt))

plt.show()

from uncertainties import correlated_values, unumpy

copt = correlated_values(popt, pcov)

Now, since we can compute the value + uncertainty for a calculation, including the correct relationship between variables, we can compute the function again, and plot a shaded uncertainty band.

def plot_with_unc(x, y, ax=None):

if ax is None:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

y_nv = unumpy.nominal_values(y)

y_sd = unumpy.std_devs(y)

(line,) = ax.plot(x, y_nv)

ax.fill_between(x, y_nv - y_sd, y_nv + y_sd, color=line.get_color(), alpha=0.2)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x_data, y_data, e_data, fmt=".")

plot_with_unc(x, f(x, *copt), ax=ax)

plt.show()

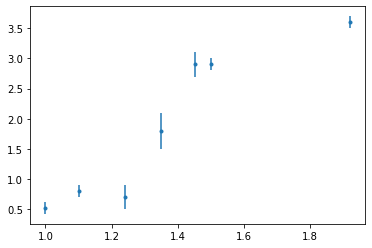

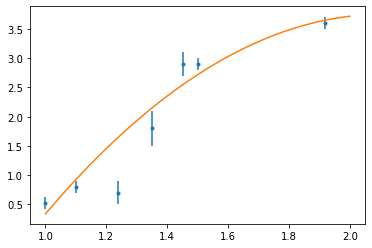

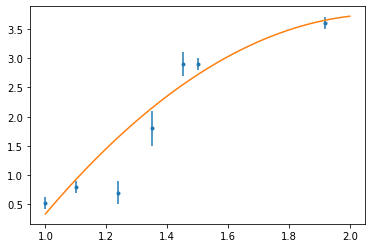

t = np.linspace(1, 2)

x = np.array([1.0, 1.1, 1.24, 1.35, 1.451, 1.5, 1.92])

y = np.array([0.52, 0.8, 0.7, 1.8, 2.9, 2.9, 3.6])

sig = np.array([0.1, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.2, 0.1, 0.1])

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x, y, sig, fmt=".")

plt.show()

Fitting function:

$$ g(x_i) = a_0 x_i^2 + a_1 x_i + a_2 \tag{1} $$If you compute the minimum of $\chi^2$, you get:

$$ \sum _i \frac{g(x_i)}{\sigma_i^2} \frac{\partial g ( x_i)}{\partial a_m} = \sum _i \frac{y_i}{\sigma_i^2} \frac{\partial g ( x_i)}{\partial a_m} \tag{2} $$We can rewrite this as a matrix expression, expanding (2) in terms of (1):

$$ A x = b \tag{3} $$sig2 = sig ** 2

ss = np.array(

[

np.sum(x ** 4 / sig2),

np.sum(x ** 3 / sig2),

np.sum(x ** 2 / sig2),

np.sum(x / sig2),

np.sum(1 / sig2),

]

)

A = np.stack([ss[:3], ss[1:4], ss[2:]])

b = np.array([np.sum(x ** 2 * y / sig2), np.sum(x * y / sig2), np.sum(y / sig2)])

print(b)

We could have been much more clever. Looking at the above expression for M, we could instead have created the powers, then raise to a matrix of powers!

power = sum(np.mgrid[2:-1:-1, 2:-1:-1])

Ap = np.sum(x[:, None, None] ** power / sig[:, None, None] ** 2, axis=0)

assert np.all(A == Ap)

Exercise for the reader: try the same trick on b.

xvec = np.linalg.solve(A, b)

print(xvec)

p = np.poly1d(xvec)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x, y, sig, fmt=".")

ax.plot(t, p(t))

plt.show()

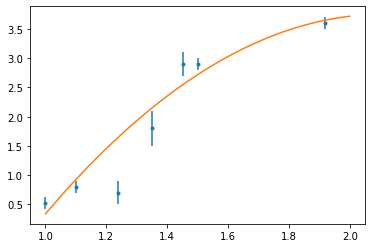

xvec = np.polyfit(x, y, 2, w=1 / sig)

p = np.poly1d(xvec)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x, y, sig, fmt=".")

ax.plot(t, p(t))

plt.show()

def new_p(x, *values):

return np.poly1d(values)(x)

xvec, _ = curve_fit(new_p, x, y, p0=[1, 1, 1], sigma=sig)

p = np.poly1d(xvec)

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.errorbar(x, y, sig, fmt=".")

ax.plot(t, p(t))

plt.show()

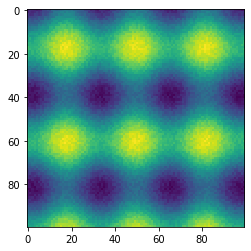

state = np.random.RandomState(42)

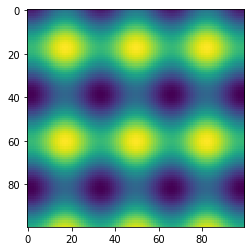

x, y = np.ogrid[-np.pi : np.pi : 100j, -np.pi : np.pi : 100j]

z = 1.2 * np.sin(2.3 * x) + 0.6 * np.cos(3.1 * y) + state.rand(100, 100) * 0.3

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(z)

plt.show()

To get this into curve_fit, we have to jump through some hoops. We need to give x and y together (it will be used by the function exactly as we give it), and we need to return a 1D array of values to compare:

Note: some older examples will show you a really odd syntax:

def f((x,y), a, b, c, d):This was more trouble than it was worth and was dropped in Python 3. Just unpack yourself if you want to unpack.

</font>

def f(xy, a, b, c, d):

x, y = xy

z = a * np.sin(b * x) + c * np.cos(d * y)

return z.ravel()

We had to return a flattened array, since curve_fit only likes flat (1D) arrays. At this point, when computing a least squared fit, the result shape does not matter, so it's okay to do. (The fact we had to build it into our fitting function is really irritating, though). We'll need to do the same thing with z, as well, since it's going to be compared with the return value:

Note:

flatten(),ravel(), andreshape(-1)all do basically the same thing, butflattenalways makes a copy, soravelis usually better.

We'll need to broadcast our 100x1 and 1x100 arrays to 100x100 so we can flatten them:

xfull, yfull = np.broadcast_arrays(x, y)

popt, pcov = curve_fit(f, [xfull.ravel(), yfull.ravel()], z.ravel(), p0=[1, 2, 0.5, 3])

Let's use the uncertainties package again, this time to provide nicer printouts of the fit values:

copt = correlated_values(popt, pcov)

for i in range(4):

print("abcd"[i], "=", format(copt[i], "P"))

Just for comparison, this is what it would have looked like if we calculated that ourselves:

for i in range(4):

print("abcd"[i], "=", popt[i], "±", np.sqrt(pcov[i, i]))

Now, the result:

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.imshow(f([x, y], *popt).reshape(100, 100))

plt.show()